Spanish Colonial Period

Spanish Colonial Period

European “history” in the Galisteo Basin begins with the first exploring expeditions, or entradas, that entered what was to become northern New Mexico. Journals and accounts are sketchy if they survived at all, and generations of historians and archaeologists have attempted to place the few descriptions in the context of modern geography. Place names often were reinvented from group to group, and only after a permanent colony was established do the cultural and natural geography come into clear focus. After failed unauthorized attempts at colonization, a royal franchise was granted to Juan de Oñate, and he established an authorized colony in 1598. Spanish colonization consisted of two parallel processes, one religious and one secular, that were often in opposition. The Spanish Colonial period is divided into two by the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the most successful instance of Native American resistance in North America. The second period begins with the Reconquest in 1692, and it ends with the independence of Mexico from Spain in 1821.

Entradas

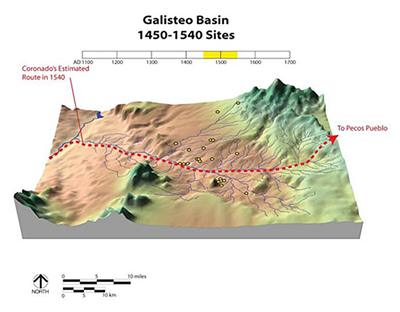

The first Europeans to describe

their visits to New Mexico were accidental tourists of the failed Cabeza de

Vaca expedition, traveling through portions of the Southwest in the 1528-1536

period while escaping captivity by Native American groups to the east. Stories they

related on their return to Mexico led to the dispatch of the 1539 Fray Marcos

de Niza expedition, famous for Estevanico’s death at Zuni (Estevanico is often

referred to as a Moor or as a Black slave) and Fray de Niza’s misperception from

a distance that mud plaster was gold. The anticipation of potential riches and

desire to further  consolidate Spain’s claims to New World territory resulted in

the Coronado expedition of 1540-1542. After learning the disappointing truth

about Zuni mud plaster, and sending Fray de Niza home in disgrace, Coronado set

up his winter base camp near Bernalillo. From that base Coronado sent out parties

that explored areas of the northern Rio Grande Valley, briefly exploring the

Galisteo Basin as a prelude to venturing out on the plains to the east in

search of Quivira and the next apocryphal source of wealth. In the Coronado expedition’s

wanderings through the basin, they noted a pueblo in ruins (circumstantial

evidence suggests that they were probably referring to the Pueblo of San

Lazaro) and several other occupied pueblos on the route to Pecos (Cicuye). The

occupied pueblos probably include two or more of the pueblos of San Marcos,

Galisteo, or San Cristobal.

consolidate Spain’s claims to New World territory resulted in

the Coronado expedition of 1540-1542. After learning the disappointing truth

about Zuni mud plaster, and sending Fray de Niza home in disgrace, Coronado set

up his winter base camp near Bernalillo. From that base Coronado sent out parties

that explored areas of the northern Rio Grande Valley, briefly exploring the

Galisteo Basin as a prelude to venturing out on the plains to the east in

search of Quivira and the next apocryphal source of wealth. In the Coronado expedition’s

wanderings through the basin, they noted a pueblo in ruins (circumstantial

evidence suggests that they were probably referring to the Pueblo of San

Lazaro) and several other occupied pueblos on the route to Pecos (Cicuye). The

occupied pueblos probably include two or more of the pueblos of San Marcos,

Galisteo, or San Cristobal.

Accounts of the subsequent exploring expeditions of Rodríguez (1581) and Espejo (1582) are ambiguous concerning Galisteo Basin communities. Both expeditions passed through the Galisteo Basin, and Pecos Pueblo is a solid referent, but their sketchy accounts of directions, distances, and sights don’t allow independent assessments of the Galisteo Basin communities at that time.

Castaño de Sosa led an abortive colonizing party to northern New Mexico in 1590-1591. From a temporary headquarters at Pecos they explored as far north as Taos, returning through the Galisteo Basin. Another headquarters was established at Pueblo San Marcos, followed by a move to the Rio Grande at Santo Domingo Pueblo. During prospecting forays from San Marcos, apparently to the Ortiz Mountain area, additional occupied and abandoned pueblos were noted. In addition to Pueblo San Marcos, historians are relatively confident that they can equate the Castaño accounts with the pueblos of Galisteo and San Cristobal, and other descriptions could be of Pueblo San Lazaro and Pueblo La Cieneguilla. De Sosa’s colonization effort was characterized as “unauthorized,” and he was arrested and his party returned to Mexico. The accumulating accounts of numerous indigenous farming communities and potential mining prospects in what would become Nuevo Mexico encouraged the decision for a royally sanctioned colonization effort.

Initial Colonization to the Pueblo Revolt

The Spanish Crown granted a contract or franchise for the colonization of New Mexico to Juan de Oñate who had become wealthy in Zacatecas. With hopes of expanding his wealth, Oñate assembled the components of his colony and began the slow journey north across a then trackless landscape. Ending their journey at the village of Ohkay Owinge (which the Spanish named San Juan de los Caballeros), the Colonists took over the pueblo of Yunque Yunque, renaming it San Gabriel. From this base, expeditions were sent out to assert sovereignty over all of the nearby Pueblo communities, to prospect for mineral resources, and to establish the boundaries of Spanish rule. Establishing sovereignty was both a secular and religious process, requiring Native populations to accept both Spanish rule and religious conversion. Oñate visited the Galisteo Basin Pueblos and placed them under his authority, but Spanish resources were too few to establish a permanent presence in the region. The Galisteo Basin pueblos escaped the violence and atrocities perpetrated by Oñate’s forces against the community at Acoma, reflecting a more passive mode of cultural interaction that was to persist up until the Pueblo Revolt.

Spanish governance of New Mexico was a revolving door of franchise assignments. The initial colony under Oñate struggled economically and in terms of internal morale (the colonists’ expectations of quality of life and riches did not materialize). Oñate was recalled, and the new governor, Pedro de Peralta officially moved his capitol to Santa Fe by 1610. The northward flow of colonists and Franciscan missionaries increased, and Spanish ranchos were established in the Rio Grande Valley from south of Socorro to the Taos Valley. While the seat of secular government was at the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe, the seat of religious leadership was established at Santo Domingo.

Tension between the secular and religious institutions was played out repeatedly in the Galisteo Basin over the ensuing century. Governors were expected to manage the colony on behalf of the King, quietly extracting their own fortunes in the process. Communities, and especially Pueblo communities, were taxed in terms of both encomienda (tribute in goods) and repartimiento (tribute in service). Encomienda and repartimiento were administered by favored colonists on behalf of the Governor, and in exchange for taxation, the governor and his representatives were obligated to provide protection for the pueblo communities. Meanwhile, Franciscan authorities were establishing missions for the conversion of the Indian population, and those missions had to be self-sustaining. Labor in support of the missions was provided by the Indian community, and to the degree that the priests were successful, it eroded the resource base of the governor and his agents.

With the establishment of the permanent colony, it quickly became apparent that the riches enjoyed by many regions of Mexico and South America were lacking, and that the major reasons for maintaining a colonial presence were to fend off other European powers and to complete the work of converting the native inhabitants to the Catholic faith. New Mexico became a subsidized colony from the perspective of the Spanish Crown, although the Governors still expected to earn their personal rewards from their administration of tribute and trade. Lacking riches, and relying on Native labor for survival and wealth, the stage was set for conflict between secular and religious authorities, with the productive capacity of Pueblo communities as the prize to be fought over.

Meanwhile, northern New Mexico was far from the center of Colonial power in Mexico, and supply and trading caravans could be months to years apart. In addition to goods, the caravans heading north brought new priests for the missions, usually fresh graduates from seminaries in Mexico that formed “recruiting classes.” From ecclesiastical headquarters in Santo Domingo, the religious administration decided how best to distribute the new arrived priests, whether replacing deceased or departing priests or establishing new missions among new Native communities. Waves of missionization resulted, as the Franciscan reach was extended and withdrawn depending on circumstance. Experience, training, fervor, and the tone of secular-religious relationships all were expressed in the mission history of the Galisteo Basin.

Perhaps as early 1613 but at least by 1616, small missions had been established at Pueblo Galisteo and Pueblo San Lazaro. Seven new priests arrived in the winter of 1616-1617, allowing the establishment of a mission at Pecos, while the mission at San Lazaro was downgraded to a visita of the mission at Galisteo. A mission was built at Pueblo San Cristobal in 1620, but after 1626 it was downgraded to visita status in favor of the larger mission at Galisteo Pueblo. The mission at Galisteo Pueblo figures most prominently in Spanish records, but missions were also present at Pueblo San Marcos and La Cieneguilla. By Royal decree, Friars were entitled to the services of ten Indian servants, but if secular accounts are to be believed, the missions were fully developed economic enterprises for the benefit of the Franciscans.

Conflict between governors and the religious authorities was tense from the beginning, and in the 1610s Governor Eulate was accused of allowing and even promoting traditional religious practice at the Galisteo Basin pueblos in exchange for favorable tribute. The secular-religious conflict theme was repeated continually, and in the early 1659-1661 the Pueblos of San Galisteo, San Cristobal, San Lazaro, and La Cienguilla were singled out as places where then Governor Mendizábal decreed that the communities should resume their ceremonial dances. The conflict involved settlers and soldiers who were responsive to the Governor, and Spaniards are reported as participating in katchina dances at San Lazaro and Galisteo pueblos, to the distress of the Friars.

The Pueblo Indians were pawns in the Spanish Colonial power struggles, and collateral damage took the form of unrelenting economic demands and repression of traditional religious belief and practice. The most important perspectives on the latter are two qualities of Pueblo culture. First, there is no clear line between the secular and sacred, so that religious belief and practice are fully integrated into daily life. Second, unlike European conceptions, Pueblo religious systems are inclusive rather than exclusionary. There is no inherent contradiction in Pueblo culture in attending mass and then participating in traditional religious practices. This duality, however, was anathema to the missionaries, who saw the abandonment of traditional religion as an absolute requirement.

The demands of encomienda and repartimiento were unrelenting, even in the face of drought, disease, and famine. Prolonged drought in 1660s and 1670s stressed Native American communities and Spanish colonists alike, and Spanish demands for tribute threatened the survival of Pueblo communities. Religious oppression was expressed in public discipline and executions of perceived traditional religious leaders, and the two stressors were the catalyst for yet another attempt at revolt on the part of the Indians of New Mexico. Instead of being isolated expressions of resistance, the revolt of 1680 was coordinated and ultimately successful.

Much of the early recorded history in the Galisteo relates to establishment of missions. Within the basin four were established at the pueblos of San Cristóbal, Galisteo, San Lazaro, and San Marcos. The church at Pueblo Galisteo was reported to be especially grand, though today traces of its existence are very subtle (photo). In addition to a quest for converts, it was desirable for the larger Spanish settlements such as Santa Fe to maintain a buffer against incursions by plains groups such as the Comanche.

A signal event in the history of Spanish settlement in the Tierra Adentro was the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. While other uprisings against European colonizers took place, that of 1680 is the most famous and was the most successful. The Europeans were expelled from all of present-day New Mexico and Arizona for 12 years. The Tano residents of the Galisteo pueblos were active participants in the revolt and the churches at the pueblos in the basin were largely destroyed. After the Spanish reconquest in 1692 several attempts were made to repopulate the Galisteo pueblos for their protective effect. This effort involved building new, though smaller, churches at Pecos and Galisteo.

Land tenure in the Galisteo Basin was largely determined by huge land grants from the Spanish Crown. The San Cristóbal and Galisteo grants began around 1800, the beginning of a long and complex history of disputes. The San Cristóbal Grant begun under Spanish rule has survived under Mexican rule, was recognize by American governments and largely is intact as the San Cristóbal Ranch today. Land speculation has always been a part of the political and social landscape.

For many years the basin was regarded as a dangerous place due to raiding by Comanches, Apaches, and even criminals disguised as natives to defer blame. While the Tano were at times staunch allies of the Spanish, they also became debt peons, disenfranchised from their lands and therefore could also become raiders.

Lippard (2010:239-280) gives an account of the latter eighteenth century travails of the Tano in the vicinity of Galisteo Pueblo. She includes an account of the mission in 1776 by Fray Antanasio Dominguez which is truly dismal:

|

“The description of the church and convent…finds no better explanation than in the lamentations of Jeremiah. The church is small. Its walls are about to fall. Half the roof is on the ground and the rest is ready to lie on the floor…The main door, which faces east, is always open, for if they move to close it falls to the ground.” |

Added to these problems were epidemics of small pox. Eventually, of course, they did leave for other pueblos including Santo Domingo, perhaps Pecos.

© New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies, a division of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs.

The Center for New Mexico Archaeology

7 Old Cochiti Road

Santa Fe, NM 87507

505-476-4404

Fax: 505-476-4448